WeChat Blueprint: How a Simple Messaging Tool Became China's All-in-One Super App

A masterclass in product evolution that Western tech giants still haven't fully grasped

I've been devouring Liang Ning's "30 Lectures on Product Thinking" and found myself obsessively highlighting nearly every page. This 2019 product management bible—now a rare find even in PDF form—reveals timeless insights about product lifecycles that most Western product frameworks completely miss.

I was particularly captivated by the WeChat chapters. They detail how a simple messaging app transformed into the digital infrastructure of an entire nation, outmaneuvering competitors at every turn. It's a masterclass in strategic product evolution that should be required reading for every product leader.

What follows is the most comprehensive English-language breakdown of WeChat's strategic evolution I've ever compiled. It reveals exactly how they:

Identified untapped user needs competitors overlooked

Built technical infrastructure that crushed first-movers

Leveraged cultural moments to drive explosive growth

Expanded from messaging to payment in ways Silicon Valley is still trying to replicate

For those who build products, this isn't just a history lesson—it's a blueprint for identifying the opportunities hiding in plain sight. For those who simply use digital products, it's a revealing look at how the apps we rely on daily are strategically designed to conquer our attention and wallets.

From Zero: The Birth

WeChat's original mission statement was disarmingly simple:

"A messaging app for people who already know each other."

This seemingly modest goal concealed an ambitious strategy to disrupt China's telecommunications market. When WeChat 1.0 launched on January 21, 2011 for iOS (followed by Android on January 24), it entered a world where Chinese consumers were still paying through the nose for basic communication:

SMS messages cost 0.1 yuan per message (~$0.015)

MMS messages cost 0.3-0.5 yuan per message (~$0.045-0.075)

WeChat offered a revolutionary alternative: free messaging and photo sharing. But here's what most people miss: WeChat wasn't first to market with this idea.

MiTalk (米聊) had already launched a month earlier in December 2010 and accumulated 500,000 users by the time WeChat appeared. The conventional wisdom says first-movers win, so why is MiTalk now just a footnote in tech history while WeChat boasts 1.33 billion monthly active users?

The answer reveals the first critical lesson in WeChat's rise: technical infrastructure trumps features.

While most product managers obsess over feature sets, Xiaolong Zhang (WeChat's creator) understood that invisible technical foundations determine a product's ceiling. Before WeChat, Zhang spent ten years building Tencent Mail—China's largest email platform—mastering how to handle massive data transfers without system crashes.

This background proved decisive. While MiTalk and later competitors offered nearly identical features, users consistently reported that WeChat simply felt faster, more reliable, and less prone to crashes. The user experience gap was subtle but profound.

Zhang's product philosophy focused on three principles:

Do one thing at a time (avoid feature bloat)

Design for extreme simplicity (reduce friction)

Fast iteration (weekly releases)

WeChat's initial version embodied this minimalism with just four core features:

Import contacts

Send messages

Send images

Set profile picture and name

No stickers. No video calls. No voice messages. Just the bare essentials executed flawlessly.

This approach makes intuitive sense: users don't want more features—they want the essential ones to work perfectly.

The Great Escape: Breaking Free From Social Limitation

By mid-2011, WeChat had successfully established itself as a reliable messaging platform. But Zhang faced an existential challenge: the product's core positioning—"for people who already know each other"—created a hard ceiling on growth.

While competitors remained focused on optimizing the messaging experience, Zhang made a counterintuitive pivot that would transform WeChat's trajectory: deliberately expanding beyond acquaintance networks into stranger-based social interactions.

This pivot wasn't obvious. Many product advisors warned that diluting the core messaging experience would alienate existing users. But Zhang recognized that WeChat's long-term viability depended on expanding beyond its original use case.

Between versions 2.2 and 4.0, WeChat introduced three features that would supercharge user acquisition:

1. "View People Nearby" – The Location Revolution

iPhone 4S, which included a built-in GPS (Global Positioning System) chip, was officially released by Apple on October 14, 2011. This was a critical inflection point that empowered location based services (LBS) apps later such as Lyft or Uber.

WeChat introduced "View People Nearby"—a feature allowing users to discover and chat with strangers in their vicinity.

This wasn't just copying Skype's "People Nearby" feature from 2010. Zhang adapted it specifically for young, urban Chinese professionals who were increasingly mobile but struggling to build new social connections in unfamiliar cities.

The impact was immediate and dramatic: daily new user acquisition doubled from 50,000 to over 100,000 by the end of 2011.

2. "Shake" – The Gamification of Serendipity

In December 2011, WeChat 3.0 introduced "Shake"—a feature letting users physically shake their phones to connect with random people doing the same elsewhere. Inspired by Badoo's "Random Chat" but enhanced with brilliant sensory design:

The gun-cocking sound effect created auditory excitement

The vibration feedback provided tactile confirmation

The randomness created a gambling-like dopamine rush

This feature became WeChat's most addictive social discovery mechanism. Users averaged 7 shakes per day, with total daily shakes reaching 100 million by 2012. International users soon nicknamed Shake "the Chinese Flirting Tool"—a label Tencent neither promoted nor discouraged.

3. "Drift Bottle" – The Emotional Connection

The poetic of WeChat's social innovations, "Drift Bottle" allowed users to write messages, seal them in virtual bottles, and cast them into a digital ocean for strangers to discover. This feature tapped into profound human desires for connection without vulnerability.

Tens of millions of bottles were thrown and retrieved daily by 2012, with activity peaking during nighttime hours when emotional loneliness is most acute. The feature created a unique form of anonymous connection that felt magical rather than creepy.

This insight reveals an important product principle: features that connect people emotionally will typically outperform purely functional ones. Success depends not just on facilitating connections, but on making those connections feel meaningful.

Through these three innovations, WeChat transformed from a simple messaging app into a social discovery platform. Its user base exploded from 30 million in 2011 to 200 million in 2012, with nearly 40% of new users coming directly through these social expansion features.

Yet WeChat wasn't the only player in this space. Momo, China's dedicated "hookup app," launched in August 2011 and reached 10 million users within six months by focusing exclusively on facilitating stranger connections.

So why did WeChat eventually dominate while Momo remained a niche player? The answer lies in WeChat's next strategic pivot—one that would transform it from a communication tool into a digital ecosystem.

Beyond Messaging: The Conquest of Physical Reality

While competitors continued optimizing for digital engagement, Zhang made another pivotal strategic decision: expanding WeChat's mission from connecting people to connecting people with the physical world.

WeChat's new mission statement evolved to:

"Bridge offline experience and business, connect people to the wider physical world."

This shift began with two seemingly unrelated features that would fundamentally alter China's digital landscape:

1. "Moments" – The Social Memory Bank

In WeChat 4.0, "Moments" (朋友圈) launched as a simple photo-sharing feature. Unlike Facebook's public timeline, WeChat's Moments were designed with Chinese cultural values in mind—emphasizing privacy, controlled sharing, and minimal public performance.

Users could share photos and updates with friends, but:

No public "like" counts were displayed

Comments were only visible to mutual connections

The chronological feed resisted algorithmic manipulation

These design choices created a space that felt authentic rather than performative. Moments became the digital equivalent of a family photo album—a place where memories were preserved rather than broadcast.

2. Official Accounts – The Media Revolution

Version 4.5 introduced "Official Accounts"—a feature allowing brands, media outlets, and creators to establish direct channels with readers. This wasn't just another notification system; it was a complete reimagining of how content reached consumers, replacing traditional SMS notifications and email marketing.

Official accounts encouraged a wave of media professionals to start their own businesses and gave rise to a large number of internet celebrities.

Ordinary people could also earn considerable income by writing through official accounts.

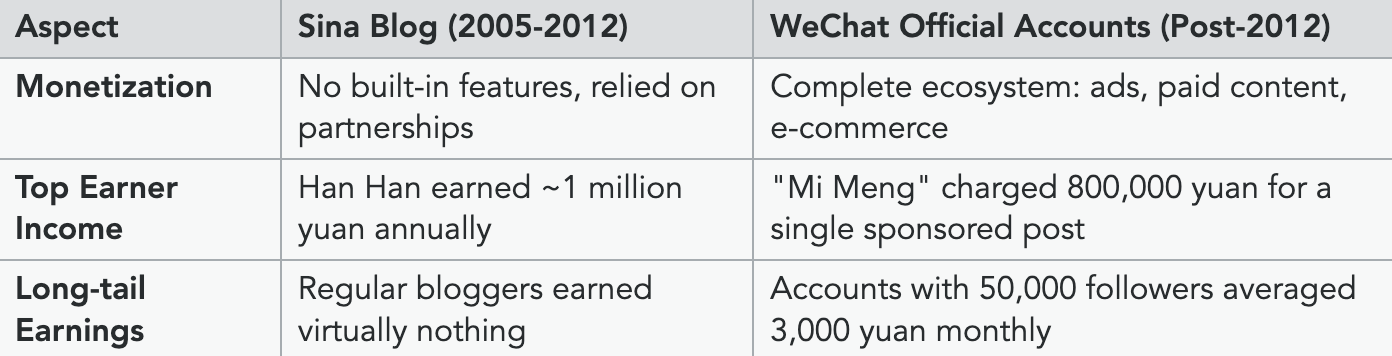

Before WeChat, Sina blog was the primary blogging platform in China. Sina Blog had over 100 million total users, but less than 100 people (0.001%) earned more than 100,000 yuan annually.

The profitable bloggers were mostly traditional media personalities (like Liang Wendao), celebrities (like Xu Jinglei), or controversial figures (like Han Han). Ordinary people found it difficult to break through.

The contrast with Sina Blog was stark:

The Social Commerce Revolution

The brilliant insight behind WeChat's expansion was recognizing that social connections could drive commercial activity. Consider how a premium bubble tea shop like Heytea leverages the WeChat ecosystem:

1. Heytea announces a new "Summer Limited Yumberry Tea" through its Official Account

2. Followers receive a notification and can share to their Moments

3. Friends see the shared post and:

Follow Heytea's account (expanding the brand's reach)

Comment "Let's grab one together!" (creating social occasions)

Visit the store, take photos, and share back to Moments (generating organic content)

This creates a virtuous cycle where social sharing drives commercial activity, which creates more social content, which drives more commercial activity.

Today if we want to pay for a bubble tea in the store, it's super simple, just scan the QR code on your mobile phone. But before 2013 in China, 60% of offline payment was still in cash.

The Payment Revolution: From Chat App to Financial Infrastructure

In 2013, WeChat faced its most audacious challenge yet: breaking into China's mobile payment market, where Alipay dominated with 82% market share. WeChat started from zero, with no apparent advantage in financial services.

The conventional wisdom said WeChat would fail. Mobile payments were Alipay's core business, backed by Alibaba's massive e-commerce ecosystem. WeChat was "just a messaging app"—what business did it have processing payments?

Yet within three years, WeChat Pay would capture 40% of China's mobile payment market, fundamentally altering China's mobile payment landscape. How did they accomplish this seemingly impossible feat?

The answer lies in a perfect storm of strategic insight, technical execution, and cultural timing.

1. The QR Code Revolution

When WeChat Pay launched in August 2013 (version 5.0), it faced a crucial infrastructure challenge: how could small businesses accept digital payments without expensive hardware?

Alipay was the first that pioneered mobile payment (2011), but it couldn't scale because it was perceived as the payment option exclusively for Taobao (online payment), or e-commerce specifically.

Alipay tried to partner with POS machines to promote mobile payment. But it didn’t really solve the cost issue for small businesses.

POS machine fees: Back then, card swipe fees were around 0.5%-1% (even 1.25% in the restaurant industry), and payments had to be settled monthly

WeChat Pay’s disruption: In the early stages, it implemented "zero-fee" subsidies (2014-2015), and later stabilized the fee rate at 0.38% (lower than POS machines), directly attracting small and micro merchants.

The use case of POS is not designed for small businesses.

POS was built for big, low-frequency transactions (like in malls or hotels) where businesses need to issue invoices. The process is complicated (insert card, enter a password, sign), so it doesn’t work well for small businesses with high-frequency, low-value transactions (like quick breakfast sales that need fast checkouts).

In comparison, QR code allows payments to be completed in just 3 seconds.

2. The Trust Problem

Despite these advantages, WeChat faced a fundamental challenge: users were reluctant to link their bank accounts to a messaging app. Two major concerns persisted:

Cognitive dissonance: "Why would I connect my bank to a chat app?"

Security fears: "Is my money safe in a messaging platform?"

The solution to this problem came from an unexpected source: a group of young Tencent employees working on a side project.

3. The Red Envelope Revolution

In what might be the most brilliant product growth hack in history, WeChat introduced "Red Envelopes" (红包) in January 2014—digital versions of the traditional money-filled red envelopes exchanged during Chinese New Year.

The feature wasn't developed through formal channels. As Wu Yi, General Manager of WeChat Pay, recounted:

"I was sitting in my office and found the workspace outside unusually noisy. I opened the door and asked, 'What are you doing? Why is it so noisy during work hours?' The young team replied, 'Remember we mentioned making a little red envelope feature? We've built it. It's really fun—want to try?'"

This side project, developed during Tencent's "20% time working on non-KPI projects" (similar to Google's policy), would become WeChat's most strategic feature.

Former Tencent executive Wu Jun recalled:

"A bunch of kids did it in their spare time — they didn’t even make a PPT."

In the 2014 Spring Festival Gala, hosts verbally guided viewers to “shake their phones” to grab red envelopes (tech teams expanded server capacity by 10 times in advance). Red envelopes was sponsored by brands like JD.com, Lufax.

You can shake 3–5 times per hour, up to 20–30 times during the entire Spring Festival Gala.

During shaking gun-reloading sound effect stimulates dopamine release.

The red envelope amount is stored in WeChat Wallet; A withdrawal button pops up right after grabbing a red envelope, prompting users to link bank cards (this is the core goal).

Larger red envelopes often need to be shared in group chats to unlock, inducing viral spread.

At the climax of the Gala, along with Li Guyi’s “Unforgettable Tonight”, WeChat sent a synchronized “withdrawal reminder,” deeply tying New Year emotion to payment behavior.

Its brilliance lay in combining cultural tradition with gamification:

1. Cultural relevance: Digitized a centuries-old tradition (giving money in red envelopes)

2. Reduced friction: Eliminated the hassle of getting fresh bills and stuffing physical envelopes

3. Created virality: Required users to share envelopes in group chats to unlock larger amounts

4. Forced adoption: Recipients needed to link bank accounts to withdraw funds

5. Gamified giving: Added randomization features where recipients received random amounts

The results were staggering:

Users sent 16 million red envelopes on Chinese New Year's Eve

Each envelope required multiple people to link their bank accounts

WeChat Pay's market share jumped from near-zero to 15% overnight

This masterful integration of cultural tradition, product design, and strategic timing transformed WeChat Pay from a banking feature into a cultural phenomenon.

This case illustrates a broader principle: financial features must be wrapped in emotionally resonant experiences to drive adoption. The most successful fintech products don't just offer utility—they create meaningful emotional connections that transform mundane financial transactions into meaningful social experiences.

WHAT WESTERN TECH STILL DOESN'T UNDERSTAND

Most Western analyses of WeChat's success focus on its "super app" status—the fact that it combines messaging, social media, payments, and services in one platform. This misses the deeper strategic insight.

WeChat didn't succeed because it crammed more features into one app. It succeeded because it:

1. Built superior technical infrastructure that created better user experiences

2. Identified natural expansion paths that aligned with evolving user needs

3. Aligned product features with cultural contexts rather than forcing Western paradigms

4. Created natural bridges between digital and physical worlds instead of treating them as separate realms

The famous ancient Chinese military strategist Mencius identified three elements necessary for victory in any endeavor:

Heavenly timing (天时): Recognizing and seizing external opportunities

Geographical advantage (地利): Leveraging existing resources and positioning

Human harmony (人和): Aligning with human psychology and cultural context

WeChat's evolution embodies all three principles. It recognized the opportunities presented by smartphone adoption (timing), leveraged Tencent's existing user base and infrastructure (advantage), and created experiences that resonated deeply with Chinese cultural values (harmony).

This strategic framework explains why WeChat succeeded where others failed, and why WeChat's success is difficult to replicate.

LESSONS FOR PRODUCT BUILDERS

For those building digital products today, WeChat's evolution offers several actionable insights:

1. Technical excellence matters more than feature innovation

Users feel the difference between smooth and laggy experiences, even if they can't articulate it

Invest in invisible infrastructure before visible features

2. Expand beyond your core use case strategically

Identify natural adjacencies that leverage your existing strengths

Create bridges between digital and physical worlds that solve real problems

3. Align with cultural contexts

Understand the specific cultural values and practices of your target users

Design features that enhance rather than replace existing social patterns

4. Make financial features emotionally engaging

Wrap transactional functions in culturally resonant experiences

Use gamification to overcome adoption barriers for utility features

5. Allow innovation from the edges

Some of the most disruptive ideas come from side projects and informal experiments

Create space for employees to pursue passion projects outside formal roadmaps

## TL;DR: The WeChat Blueprint

For those who made it this far, here's the condensed version of WeChat's strategic evolution:

1. Start with technical excellence in a focused area (messaging)

2. Expand social graph beyond existing connections (stranger social)

3. Bridge digital and physical worlds through media and social commerce

4. Transform utility features into cultural phenomena (payments)

WeChat's journey from simple messaging app to digital infrastructure demonstrates that product evolution isn't just about adding features—it's about strategically expanding into adjacent spaces that create compounding value for users.

Whether you're building the next great app or simply trying to understand how technology shapes our lives, WeChat's evolution offers a masterclass in strategic product thinking.

I'd love to hear your thoughts. Have you observed similar principles in other successful products? Or do you see flaws in WeChat's approach that I've overlooked? The conversation continues in the comments.

This is one of the most insightful breakdowns I’ve read on WeChat. The distinction between feature set and technical infrastructure is so often overlooked, especially in Silicon Valley where MVP culture sometimes sacrifices quality for speed. That “red envelope” anecdote alone deserves to be studied in every product strategy class.